Look around the offices of SnapDeal, an online coupon business, and it's not hard to see all the signs of a thriving venture.

A young staff full of drive and ambition, a tote board on the wall tracking new customers, one about every second.

But SnapDeal isn't in Silicon Valley — it's in New Delhi, India.

Kunal Bahl, 27, and his partner, Rohit Bansal, launched SnapDeal in February 2010. They're already the No. 1 e-commerce retailer in India.

“SnapDeal is a very simple concept,” Bahl said. “Every day there is one attractive deal and people come to the website, buy the deal and go use it at the merchant.”

Bahl's company has created 300 jobs — and counting. But he sometimes wonders "what if …?" What if the country where he got his education, where he helped start a company while still in business school, had let him stay?

“I put my chips in the American basket and said let me try my hand here,” said Bahl, who earned an engineering degree from the University of Pennsylvania and a business degree from its Wharton School.

But Bahl's visa ran out, and he took his skills back to India.

The United States issues only 85,000 of the so-called H1B visas for highly skilled workers each year. And these expire after six years.

There's broad agreement that the current immigration and visa system needs reform — that's going to need to come from Congress.

Still, the State Department does what it can to help encourage entrepreneurship around the world.

The San Francisco Bay Area — the home of Silicon Valley, Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley — has always been a magnet for the best and brightest from foreign lands, but now many are wondering, why do U.S. immigration officials make it so hard for them to stay?

“We're strengthening our competitors, we're weakening ourselves,” said Vivek Wadhwa, a visiting professor at Berkeley and research associate with the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School. He has been warning of a "reverse brain drain" for years.

"There are a lot of very good human beings who are unemployed, who have lost their jobs,” Wadhwa said. “It's easy for them to blame foreigners. What they don't understand is people like me, when I came to this country, I came to study. My first company created 1,000 jobs. My second company created 200 jobs.

Wadhwa's research found that between 1995 and 2005, 25 percent of startups in Silicon Valley had at least one immigrant founder. And those startups created nearly a half-million jobs.

U.S. immigration rules are big roadblocks for the enterprising foreigners.

Martin Kleppmann, German co-founder of San Francisco startup Rapportive, which shows users everything about their contacts from inside their email inboxes, said everyone has stories to share about how painful the visa process has been.

“You're trying to quickly engage with customers — make sure that everything's developing, and at the same time, you've got this huge distraction — worrying whether you're going to get kicked out of the country,” said Kleppmann, who has a bachelor's in computer science from the University of Cambridge and studied music composition at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama.

At a gathering of nearly a dozen young Silicon Valley entrepreneurs recently, more than half said they think they’ll end up back in their home countries rather than staying in the U.S. because of visa issues — and they would take jobs with them when they leave.

Immigration officials often don't even understand the technology business.

Kleppmann drew laughs from the group when he explained an example.

“In our case — we got a beautiful letter from the immigration service asking to prove that we had enough warehouse space to store our software inventory. We don't even have boxes of software, it's all on the Internet."

Sakina Arsiwala of India co-founded San Francisco-based Campfire Labs, a startup that wants to "change the way people think of social interactions in the real world and online."

“Why deal with all this, you know, old school immigration systems, just go where you're wanted, you know?” said Arsiwala, a software engineer who formerly headed YouTube's international business for Google. She studied at the University of Mumbai and San Francisco State University.

Bahl went where he felt welcome. Close to family in a newly vibrant India.

“There is no ‘either or’ relationship between the American dream and the Indian dream, Bahl said. “They can both exist, it's just that the guys who are building the Indian dream right now could have been part of the American dream, too.”

In an interesting twist in Bahl's case, he's looking into launching SnapDeal internationally, including in the U.S., and hiring Americans to help him do it.

Source - http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/41894670/ns/business-consumer_news/

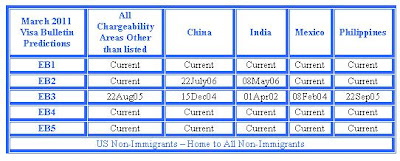

Here is the Prediction for EB2 Category cutoff date movement for Fiscal Year 2011. Basis for this prediction is simple calculations (see below) which is done based on available data i.e. visa statistics recently released for CY 2010, PERM data published by DOL for CY 2010, latest trend on Trackitt for EB2 cases and other published data by USCIS. Demand data for each dependent category is predicted and explained in calculations below. This data is further used to calculate spillover that would be available for EB2 category. Dates are predicted based on visa allotment available each year for each country and total spillover that is expected in FY 2011. In each case, Optimistic, Realistic and Worst-Case scenario is predicted.

Here is the Prediction for EB2 Category cutoff date movement for Fiscal Year 2011. Basis for this prediction is simple calculations (see below) which is done based on available data i.e. visa statistics recently released for CY 2010, PERM data published by DOL for CY 2010, latest trend on Trackitt for EB2 cases and other published data by USCIS. Demand data for each dependent category is predicted and explained in calculations below. This data is further used to calculate spillover that would be available for EB2 category. Dates are predicted based on visa allotment available each year for each country and total spillover that is expected in FY 2011. In each case, Optimistic, Realistic and Worst-Case scenario is predicted.  We have added new sections for

We have added new sections for  Based on currently released statement by Mr. Oppenheim on 12,000 available unused visa numbers from EB1 category to EB2 for FY 2011, we are revising our Predictions for EB2 Category for FY 2011. We are reporting worst-case, realistic and optimistic scenarios for our predictions.

Based on currently released statement by Mr. Oppenheim on 12,000 available unused visa numbers from EB1 category to EB2 for FY 2011, we are revising our Predictions for EB2 Category for FY 2011. We are reporting worst-case, realistic and optimistic scenarios for our predictions.